On Wednesday, October 30th, data on the GDP of the Eurozone and, simultaneously, of the United States were released. Let’s analyze the main results.

Across the Atlantic, growth has not stopped. GDP shows a year-on-year increase of +2.8% in real terms. With two additional good news. The product deflator grows by +2.2 points, indicating that the Fed's anti-inflation cure has been successful. It is the first time in over twenty years that an increase in interest rates has not led straight into recession. The soft landing has succeeded and Jerome Powell can take credit for an action that, for example, Greenspan failed to achieve in 2000. Secondly, anticipated (real) consumptions are expected to grow by +3.8 percent. This is also good news for the economy, because the American savings rate is almost at his historic lows, around 2 percent, which means that the path of consumption, which has always been the primary economic engine of the United States, is not yet threatened. This is supported – unfortunately – by more credit card debt (over 8,000 dollars per capita) than wage increases, but the tight labor market, where it is difficult to find people to employ, should sooner or later convince employers to pay their employees better. Speaking about that, on the same day, October 30, the provisional data on pay slips was released (each pay slip corresponds to a salary, but not necessarily to a full-time employee), which once again exceeded 200 thousand units. The real economy is hiring and doing so well that, based on this news, Wall Street has retreated from its historic highs, almost as if to predict that the next rate cut might not be “jumbo” like the first and previous one. Joe Biden’s administration reached the end of the mandate in good shape, at least on the economy.

Less positive, however, were the subsequent data for the month of October, with the creation of only 12,000 jobs, the smallest increase since December 2020, also due to two hurricanes and major strikes.

It's a very different story on this side of the Atlantic Ocean. Here the economy is suffering. Although many have commented that Europe is showing signs of recovery, we are much more cautious. In fact, the Eurozone's GDP grew by just 0.4% in the third quarter, with annual growth of 0.9%. In the EU-27, the quarterly increase was 0.3%, identical to the previous quarter, and the annual increase stopped here too at 0.9%. If you think about it, for a continent like Europe, which should recover at least one point of growth compared to the United States, the distance has instead increased, because between the two continents the instantaneous growth gap would seem to be 1.9 percent, to the detriment of Europe.

Europe already has higher tax pressure and greater spending on the welfare state than the United States. It has a greater aging population and less dynamic and efficient stock markets than the American one. We are definitely outside of any idea of a path to recovering the gap. Whether the solution is the "Draghi cure" of 800 billion a year of public and private investments in infrastructure, defense and innovative technologies or whether another one is conceived, this should be the most important point of the economic agenda of the recently established Commission, to be reconciled, as far as realistically possible, with the priorities of the two transitions.

Germany has avoided a technical recession thanks to government measures and household spending, showing a 0.2% quarterly increase in GDP in the third quarter. However, on an annual basis, German GDP still fell by 0.2%, which becomes +0.2% only if the raw data is corrected for the number of working days. In the third quarter, however, the auto crisis in Germany had not yet reached emergency levels, which is why it is possible that the fourth quarter will return to the red. Germany remains the sick man of Europe for having bet all its cards on the eastern markets, where its products are now having difficulty. Replacing those exports will not be easy, also because the most reasonable hypothesis would be to increase domestic demand, which is not easy without sending the public budget into deficit, something that the Germans tend not to do.

In France, a feeble recovery continues: the Olympics have stimulated the economy, which grew by 0.4% in the third quarter, thanks to domestic consumptions. On an annual basis, French GDP increases by 1.3% and France is the only major country that exceeds one percentage point. It is difficult to think that it will maintain it, given that French growth is based on a public budget that Macron has brought down to -5.5% of GDP in 2023 and to -6.1% in 2024. These are "Italian" numbers that we were not used to seeing headed by "Grandeur". The upcoming maneuver, worth 60 thousand billion, is unlikely not to impact growth. Its size is sufficient to produce a technical recession: not a good end for the last mandate of President Macron, a skilled leader in politics who has however proven less effective than expected in economics. The middle class had promoted him as President for his age, his energy but also because he came from the world of investment bankers: a guarantee to avoid risks for the economy that was ultimately disappointed.

Spain continues to surprise with its robust growth: +0.8% in the third quarter, with a significant annual trend: +3.4%. Spain is a demographically younger economy than the European average. It was ahead of the curve in the energy transition and it is able to offer citizens and businesses low-cost energy, which leaves room for private spending that elsewhere has to pay heavy bills. It is also taking advantage of the international recovery in tourism. However, in the fourth quarter we will see a decline, because the climate disasters that have hit it will stop the GDP in a significant portion of the country.

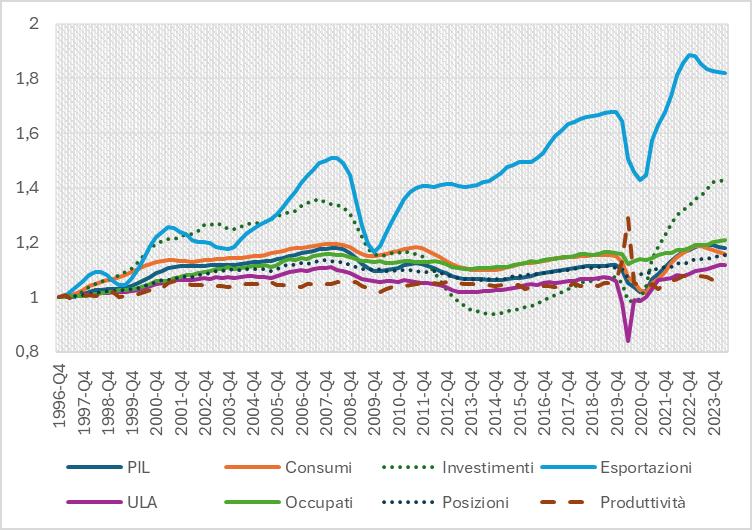

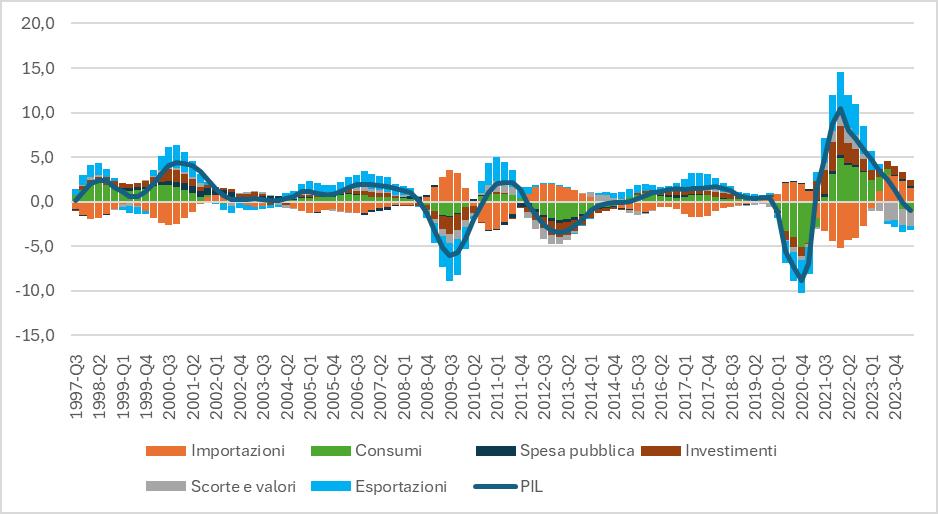

The Italian economy, on the other hand, remains stagnant: the GDP is completely unchanged compared to the previous quarter, while it grows by 0.4% on an annual basis. This raises many doubts about the possibility of reaching the ambitious growth target of 1% for 2024, as envisaged by the government. Istat attributes this “zero growth, without the decimal point” to growth in the tertiary sector, a slight contraction in agriculture, forestry and fishing, and a significant decline in industry, with the automotive sector in particular difficulty. All true, but we cannot forget that this result is not only the result of the economic situation. It is also the result of the particular growth model of the last twenty years.

If you look at figure 2, you can see that the decline in Italian GDP growth is nothing new at all. The post-pandemic rebound in consumption (a sort of revenge spending after the pandemic) ended a couple of quarters ago. Investments have reduced the push while waiting for the PNRR, which is constantly delayed, and the pull of exports is no longer there. In other words, exports in this situation are already asking a lot to “hold up”, but it is almost impossible to “increase” their contribution. The immediate consequence of “zero growth without a comma” is that the economic maneuver could be insufficient and the new European rules are not a joke. In case of insufficiency, “one-offs” do not apply, the pact requires structural interventions, i.e. increases in revenue or reductions in expenditure that are permanent and not temporary. The less immediate consequence is that we can safely shelve the idea that “after the pandemic” the economic miracle has returned. To produce sustained growth in the medium term, we need to return to traditional tools: those of investment and innovation. Two words in which Italy has never expressed itself at its best, and in the last twenty years, to be honest, it has seemed rather stuttering.

© Riproduzione riservata