Soon another large Italian company could disappear from the Milan Stock Exchange listing. It is Saras, which manages the Sarroch refinery in Sardinia. A plant with a capacity of 300 thousand barrels per day, in an excellent strategic position in the Mediterranean, founded by Angelo Moratti in 1962. The company has in fact turned the page, ending up in the orbit of Vitol, a Dutch Swiss energy group, with a thriving business of about 500 billion dollars a year.

We do not discuss the business side of the operation, because entering the portfolio of a global energy operator could even improve the business prospects and dispel the fears, at the moment legitimate, of job losses. Instead, we are concerned about the impact of the deal on the credibility of the Italian stock market. The Italian stock market is full of imperfections and backwardness compared to the advanced Anglo-Saxon markets. An excessive concentration in some industries; a very slight share of public companies (i.e. companies with widespread shareholding), which would be 13% against 80% in the United States.

Then there is the question of the low free float: i.e. the percentage of capital to be issued on the market at the listing time is very little in Italy. On Euronext-Milan 10 percent of the capital is enough. The true global investors like instead put the money on scalable companies with widespread shareholding like Microsoft, Apple and others. And they are the ones that Milan almost does not own, we would say stubbornly, condemning the Financial City of this European town to a low ranking in the financial world. One might ask: why? Among other things, in these years and months Italian companies are trying to convince the small investors of their social responsibility, by certifying their ESG compliance, while the structural data of the stock market continues to be unconvincing. Mainly in the past, the Italian stock market has been used more to raise funds from the public than to distribute the satisfactions coming from the investments.

The consequences of the Saras-Sarroch operation will go towards the delisting of Saras, with little satisfaction for the thousands of small investors who had joined the placement at around 6 euros and who will probably realize 1.75 euros per share. Even calculating the dividends collected in the meantime, the operation for the small shareholders will close in loss. In fact, the delisting will highlight the existence of two categories of shareholders.

On one side, there is the original family, that have already achieved a good valuation with public placement in the 2006. On the other side, the majority of these underwriters, who will get out of the investment with what little the shares will be worth now. Treating the stock market in this way, by influential representatives of Italian capitalism, really benefits only a few. The stock market is part of the financial markets. Not the biggest, but not the most negligible. The credit market is the most important and we can recognize that, after the changes that have taken place over the decades, the Italian banking system does not look bad in the European panorama. The company equity market is instead the stock market, at least the segment accessible to the public. A mature stock market would be more attractive for small and medium enterprises; it would be a formidable channel of financing for many long-term investment projects with difficulty in being bankable; it could channel resources from institutional investors, such as pension funds, towards productive investments and real jobs, while as is well known Italian pension funds prefer to limit their domestic equity exposure. They can’t really be blamed. Wall Street is also a gigantic attractor of savings from the rest of the world that is invested in the United States.

It will be said that Italian savings are sufficient, given the proverbial qualities of the Italians, but it is not true, because much of that savings is absorbed by the financing of the public debt. Often the model of family capitalism has been cited as an alternative to that of the stock market. We think that is not the case. A large and efficient stock market would increase the investment opportunities also for the entrepreneurial families and reduce the recurring temptations to use the stock market as an opportunistic financial resource. Here, an efficient stock market with more public companies listed would make the difference and the first ones to care at it should be the prominent exponents of Italian capitalism.

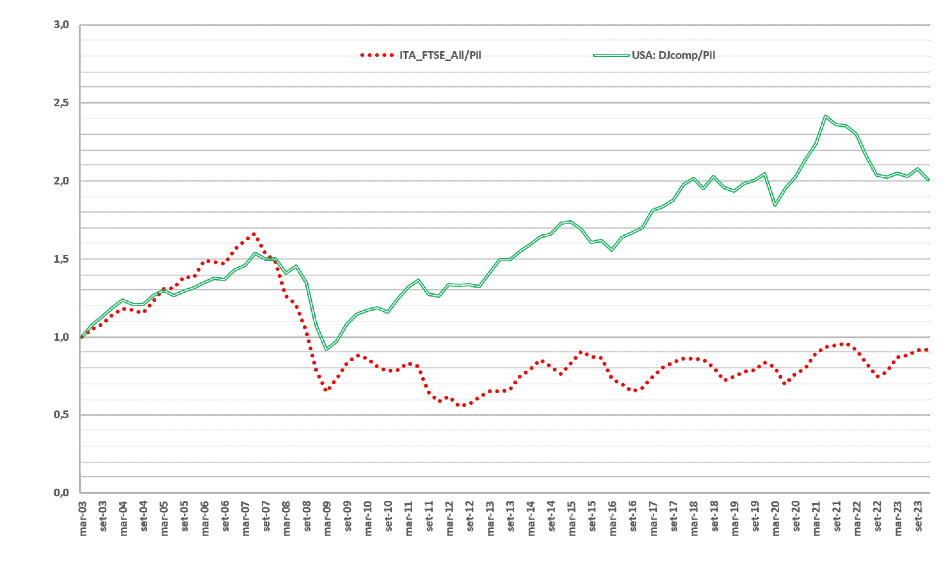

As an example, we did the exercise of comparing the ratio between the stock market indices and the American and Italian GDP .

In terms of index number, from 2003 to today (twenty years in total), the American ratio has gone from 1 to 2, while the Italian one, after an initial rise, has fallen back and is below unity, having paid less dividends than the American stock market and having as denominator a GDP that has grown far less than the American. A stock market like the Italian one is not appealing, does not grow the economy, does not grow the wealth of the Italians. What are we waiting for to reform the stock market in Italy? Anemic economic growth is telling us the right time is now.

© Riproduzione riservata