Cosa può essere la nuova India per l'Europa e la Cina? Un nuovo partner strategico o un rivale globale?

It is quiet recently that the European Union has finally delineated a strategy for its bilateral relationships with China. In March 2019, it published an official document “UE-China: a strategic outlook”. For years, Member States have lined up on two fronts, alarmists or accommodating, struggling to reach a common position. However, nowadays, China has gone from being defined as a “strategic partner” to a “systematic rival”.

Over years, many experts have remained unheard like some sort of Cassandras always bearing bad news. Often ignored, their warning have often been voluntarily ignored and experts dismissed as too apprehensive when they solicited European summits to recognize Beijing’s nature and to take a more proactive position towards it. However, where the experts failed, the market succeeded. It took the complete destruction of the European manufacturing industry of solar panels at the hands of the Chinese industry first, and, later, the surpassing of the Chinese robotics producer Midea over the German one, Kuka, and, finally China’s most recent debut as an aerospace manufacturer, to give the final shake to Brussels’ bureaucrats . Therefore, this realization came at a high price.

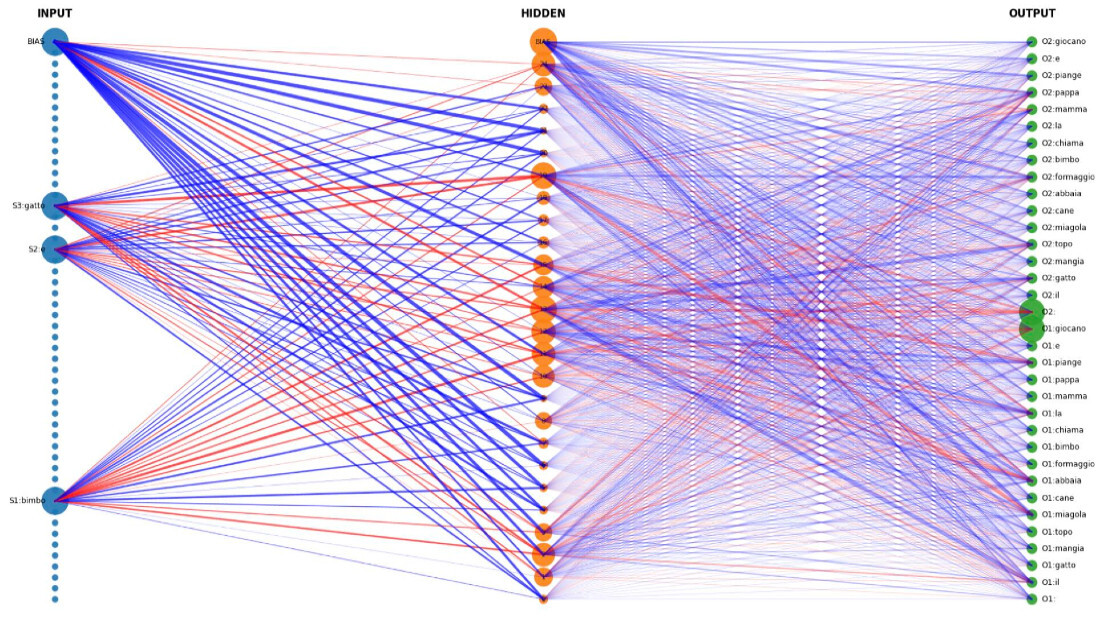

Nevertheless, while Europe seems to have finally noticed of China’s rivalry, China itself seems to be dealing with a similar realization towards India. Infact, lately, a multitude of Chinese experts have been lamenting about the scarce attention given to the economic growth registered in the last two decades in India (Figure 1). So that, some have defined the Indian continent as the real new “enemy” of China, instead of the long recognized Japan. And in the meantime, Europe, exhausted by the exercise of defining its relationship with China, it is struggling to maintain constant relations with the new India. What can India be for Europe? Does it have to deal with a strategic partner or again with another systematic rival? Or, can a third way be outlined?

What is extremely clear, is that we can already talk of a “new” India. It is about a change triggered by the first Modi government, in 2014, and that, in all likelihood, will be consolidated during his second government which started in 2019. A change of course that consists of a concrete commitment of what is the biggest democracy in the world to, not only to carve out a place in the sphere of international politics but to shape these politics. In fact, India is actively trying to move from a balancing power to a driving power, from a non-aligned country to a country that is consistent in outlining its position on various fronts.

What is particularly striking about modern India is its renewed assertiveness in terms of international politics. In its immediate neighborhood, India attempts to transform the Asia-Pacific region into the "Indo-Pacific" region, causing Putin's irritation in Russia and a certain competitiveness for regional supremacy. At the same time, guided by a certain ambition, India also looks well beyond its immediate neighborhood, to Africa. In fact, in the Dark continent its presence is growing and the goal is to balance the Chinese hegemony, and, to Latin America, where although the contacts are recent, the Indian commitment to collaboration is growing.

In relationship with Japan, India intends to consolidate an increasingly equal relationship, based on many common points they share. The two countries believe in democracy, rule of law and human rights. And it is on these principles that New Delhi plans to diversify its relationship with Tokyo with which, for now, it has always cooperated successfully on an economic level. However, its approach to China is different. If on the one hand India leverages Chinese capital to support its progress, on the other hand, it tries to position itself as a valid alternative to China. India focuses on fair, truly bilateral relations and into avoiding overlaps of power.

Curiously, while for China it is still in doubt how it intends to relate to an increasingly prominent India, for India it is an already well-established rivalry. It is in fact on the border war of 1962, in which the two border regions, Aksaj Chin and Arunachal Pradesh, were contested, claimed as part of Kashmir by India and as part of Xinjiang by China, that India bases its national defense strategy. On the contrary, China seems to have noticed only now that, unlike Japan, India is a state that possesses nuclear weapons (Figure 2), which under the direction of Modi is increasing its stature in world politics and that, ultimately, the own project for the new Silk Road will only exacerbate their rivalry.

Just back in 1950, China and India were at par with each other. And even in 1978, their per capita GDPs were not consistently distant, China’s GDP was $979, and India’s one was $966. In fact, China, who is now leading, used to be at a disadvantage on some aspects on development. It is only with the coming of Deng Xiaoping precisely in 1978 that Chinese economy started its booming. Today, China's per capita income today is about 4.6 times than that of India (Figure 3).

There are few evident reasons to explain these developments. The first one is their respective form of governance. While India is a democracy, China is far from being described as a democracy and many have been busy trying to conceptualize what type of government rules it. This is an important aspect as it impacts on the decision making of the country. India is a consolidated democracy. This means that the country has to deal with the complexity and messiness of a democratic decision making that has to put together federal and regional levels of decision making. China, instead, with its centralized decision making encounters few impediments to any reform it wants to implement.

A striking example of the “freedom” of maneuvre the two countries enjoy is infrastructure expenditure.This an extremely important sector given the fact that productivity growth heavily depends on infrastructure investment. For India, spending in this field is extremely difficult because of its divided politics, that make any decision very slow and bumpy at best. According to some estimates, the inefficiency caused by the democratic process and the consequent lack of infrastructure development, has costed to India a reduction in the annual GDP growth of 1-2 %. This is a foreign situation to China which is not a democracy. Therefore, the Communist Party is free to implement whatever infrastructural project it has in mind. In fact, the most recent Chinese story is dotted with projects in this field and explain its economic lift off . And yet, it is precisely the form of governance that could make a difference in the longer term. In fact, the history of democracy India consolidated over the past 60 years, gives the country some foundation for stability and adaptation to eventual crises. The same cannot be argued for China which will soon have to face a political transition whose direction is not predictable and this could make its development vulnerable .

Another important aspect is the hardware/software divide between the two countries that has been developing over the years and that, until now, has constituted their respective fortune and that is now turning into a challenge for both. India has been thriving in software and IT services. In fact, today, this is the fastest growing sector in the Indian economy and it is developed to a point that it has become one of the main symbols of globalization, just like McDonalds and MTV. Bangalore has become the Silicon valley of India, attracting highly skilled workers and investments. However, its growth is limited by a very weak infrastructure, frequent power cuts and traffic jams Therefore, the problem in India is the presence of a software not backed up by the presence of hardware. On the other hand, China faces a completely opposite obstacle. As we have previously mentioned, China has developed considerably in terms of hardware, therefore it does not lack of infrastructures and technologies, but it is not as advanced as that in terms of softwares.

This state of play poses both obstacles to their respective economic growth but it also sheds a light on their complementarity. Lately, India has tried to put a remedy to its problem by launching its most ambitious infrastructure project, a plan to widen and pave 40,000 miles of highways, to be financed with US$6.25 billion. Instead, China has started to recognize that there is a dyscrepancy between their futuristic cities and the lack of indipendent culture. Over the years,on one hand, India focused on services while, on the other hand, China focused on manufactoring. However, it is important to mention that most of the big players in India’s software industry, like Satyam, TCS and Wipro, have long ago set up offices in Shanghai or Beijing. Their assumption is that there will be an increasingly Chinese growing market since China is forecasted to become one of the biggest consumers of software services in the world. Chinese companies have not shown the same readiness in establishing headquarters in India. Until now, the only notworthy example is Huawei who sees in the relatively low production and consuption of consumer eletronics in the country combined with a rising middle-class an important potential market (Figure 4). However, it remains to be seen what the so called “dragon”, China, and, the so called “elephant” will do of their complementarity.

According to the OECD, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the country-continent, India, will long be unchallenged as a large, fast-growing economy. The Paris-based think tank states in a report that while the Chinese economy slows down due to its tensions with Trump's America, Indian GDP growth will settle at around 7.5%, growing compared to 7.25% the previous year. Moreover, despite the fact the two powers, have, today, roughly the same population, by 2050 the demographic scenario will change considerably (Figure 5). While India will have around 270 million more citizens, China’s population will decrease by 30 million. And, what is more important is that the Indian workforce population is expected to reach the Chinese one, around 800 million people.

Under the assumption that ultimately rapid growth will slow down for both, China has experienced high growth before India and, therefore, its run might slow down first. And if all the above is not enough to talk about an overtaking of India on China, it is important for Europe not to ignore India's will to be a careful and different interlocutor. If nothing else, not to repeat the same mistakes made with China. If only because, if China recognizes India as a rival, it would be useful to have close relations with the rival of our "systematic rival", China. Ultimately, this is another important test bench for the EU foreign policy, an opportunity to learn but also to build up its reputation.

© Riproduzione riservata