I carefully read back the new data released by ISTAT on the demographic and labor market outlook for 2050. By that year, the retirement age will rise to almost 69—precisely 68 years and 11 months, compared to 67 today. Meanwhile, the share of the population aged 65 and over will increase from 24.3% in 2024 to 34.6% in 2050 (source: ISTAT, National Demographic Forecasts 2024–2050), while the 15–64 age group, i.e., the working-age population, will decline from 63.5% to 54.3%.

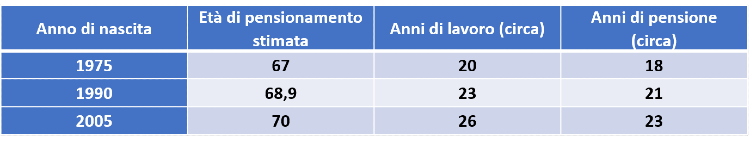

Amid this progressive shrinkage of the potential workforce, projections simultaneously show an increase in labor force participation among older age groups. According to Eurostat and ISTAT (Labor Participation Indicators 2023), the share of employed people aged 55 to 64 will rise from around 61% today to nearly 70% by 2050. In other words, the slowdown in generational turnover will be partially offset by a longer tenure in the labor market. These clear, official numbers describe a country that lives longer, is older, and is more exposed to the elements. But when I look at them through the eyes of someone who studies duration, I don't just wonder at what age we'll retire. I wonder how long we'll stay there. Because behind these figures lies a story of economic, social, and human time that concerns us all. And it's no longer enough to look at the age threshold: we need to look at the overall shape of time, how it lengthens, empties, or recomposes itself within and after working life. So I tried to read those numbers differently: not as demographic curves, but as lived time. What happens if we try to measure not when someone retires from work, but how long their life is afterward? Considering three reference generations—1975, 1990, and 2005—and starting from official projections, I estimated for each the retirement age, total years of work, and years of retirement.

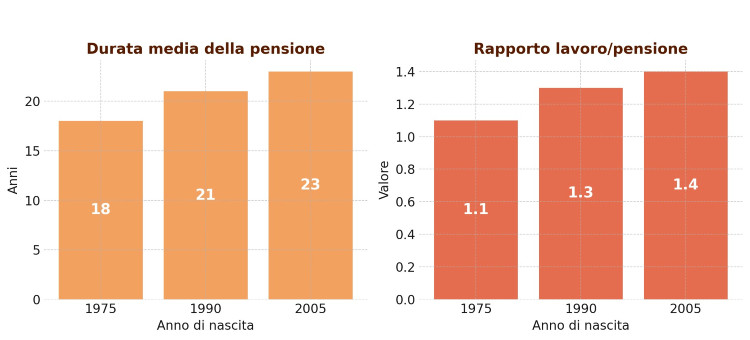

Three Generations Compared

- Those born in 1975 will retire around age 67, with approximately 18 years of pensionable time.

- Those born in 1990 will retire just under age 69, but will live an average of over 21 years in retirement.

- Those born in 2005 will retire around age 70, with approximately 23 years of life remaining.

The retirement age is rising, but the duration of retirement is growing even more: time "outside of work" is expanding more rapidly than time "inside" it. It's as if life has shifted its horizons a little further, without the economy having yet learned to keep pace. Behind these numbers, there's not just a shift in phase, but a change in pace. The "active" part of life is no longer sufficient to contain everything that comes after: a new space is growing, suspended between freedom and uncertainty, the scope and effects of which we haven't yet fully understood. Younger generations won't just have a longer pension: they'll have more time to manage, more choices to make, more years to support, financially and mentally. Retirement is no longer a leave of absence from work, but a new season of life, often as long as the previous one, yet we continue to think of it with the categories of an era when it lasted ten or fifteen years. This is where the real divide arises: between the time we live in and the way we continue to imagine it.

The changing ratio

So, to truly understand how longevity is reshaping life's time, it's not enough to look at the age at which one retires from work. We need to ask ourselves how long the life that follows lasts, and what balance links the productive and the enjoyable. In other words, it's no longer the "when" that matters, but the "for how long." At this point, I tried to go further: I wanted to calculate a new indicator, the ratio between actual years of work and expected years of retirement, to understand what really happens to time when we measure it instead of taking it for granted. For the 1975 generation, this ratio is approximately 1.1, for the 1990 generation, 1.3, and for those born in 2005, it reaches 1.4. In simple terms, this means that for younger generations, every year of active life will mean almost a year spent out of work, not because people work more, but because they live longer. It's a measure of the new balance of economic time: how much productive time is needed to guarantee the time of freedom. It's not just a numerical comparison, but a different way of interpreting duration, as a ratio between what generates income and what consumes its value over the long term. In other words, the ratio values don't indicate that people work more, but that work and retirement grow together within an overall longer lifespan. Economic time is rebalancing, not extending.

Average retirement duration and work/pension ratio for three generations

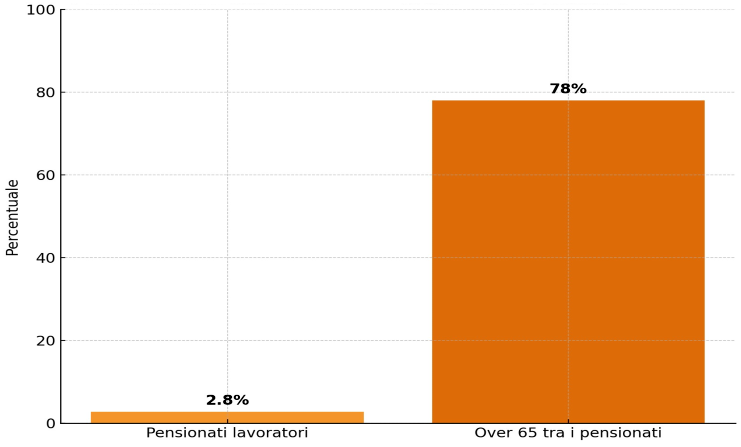

These numbers don't just describe a change of phase, but a change of structure. The "active" part of life is lengthening, but the "post-work" phase is growing even more, almost equaling it. This proves that economic time is no longer symmetrical: life continues to expand, but its productive part is not growing at the same rate. A new balance is born, one that affects not only pension accounting, but the entire economic architecture of time. Each year of work no longer represents just income, but becomes generative time, capable of financing and giving meaning to the part of life that follows. From this perspective, retirement is no longer an end, but a form of continuity: the outcome of a time that extends, transforms, and must be rethought as a resource, not a cost. This new relationship between working life and post-work life is not just a theoretical exercise: reality is already anticipating it. Indeed, an increasing number of people are extending their "active" time beyond the formal retirement threshold, in a sort of economic and identity continuity that is changing the very concept of working age. According to the most recent INPS surveys (2023 Observatory), approximately 737,000 retirees continue to work, equal to 2.8% of the total workforce. Of these, over 575,000 are over 65: a share that confirms a structural trend. More and more people are remaining active even after retirement, in self-employed, flexible, or occasional forms.

Retirees who continue to work

In its focus on "Are We Aging Well?" (2023), ISTAT reports that the participation of over-65s in the workforce is steadily increasing, especially among self-employed workers and graduates, and that the segment of those engaged in occasional or irregular work is expanding. It's clear that all this isn't just an economic response, but a cultural adaptation of time. For many, continuing to work beyond retirement age represents a form of continuity, belonging, and personal balance. As the report "Elderly People in Metropolitan Cities" (ISTAT, 2023) also highlights, over-65s are increasingly contributing to economic and social life: through volunteering, family support, and micro-activities. It's a time "in between," suspended between work and retirement, which eludes the traditional distinction between "active" and "retired," but which now constitutes a stable component of the new life cycle. It's not just an actuarial formula: it's a different way of interpreting economic life. Understanding how much "active" time is needed to support "passive" time means learning to measure life in a new way as a balance between income, activity, and freedom. It is the measure of how much "economic time" each of us is called upon to generate to sustain not only our own future, but also that of the community.

The time economy has lengthened, but has not adapted.

This exercise stems from a simple but crucial curiosity: to see what happens to time when it is translated into duration, not age. And this is where the deepest contradiction of our system emerges: "active" and "passive" time no longer balance each other; they expand in different directions. It is as if society has extended its life horizon without rewriting the structure that supports it. Today, a 40-year-old woman can realistically expect to live beyond 87, but it is unlikely she will have a continuous contributory career of 40 years: periods of part-time work, interruptions for care, and discontinuous work reduce "productive" time compared to "lived" time. Thus, while biology expands, the economy of time remains compressed. A system built for an average lifespan of 75 years must now support one of 90, with the same rules and the same contribution bases. It's as if we've added a chapter to life, but haven't yet decided who will write it: the state, the market, or each of us. Other countries have begun to measure this disproportion. In Japan, for example, they now speak of a "longevity economy," an economy that recognizes duration as a productive factor, not just a social cost. In Germany, pension savings systems are being redesigned based on the average retirement age, not the legal age. In Italy, however, the debate remains stuck on the "when," while the "for how long" continues to elude us. But the challenge isn't just accounting; it's above all cultural. It concerns the perception of time itself, the ability to consider it an economic variable, to be invested and not just consumed. A society that lives longer but still thinks short-term risks producing a new form of fragility: the illiteracy of duration.

A new geography of duration

This is why I speak of a new geography of time. It's not an image, but a concrete necessity: understanding how to redistribute the ages of life in a context that lives longer but is not yet designed to last. In this geography, sustainability goes from being a simple financial balance to a balance between different times: that of work, that of care, that of rest. Lifespan is no longer an external variable: it is now a structural part of the economy. Imagining a long-lived society therefore means redesigning the relationship between time, income, and meaning, finding tools that transform longevity into a resource, not a burden. We need a policy of time that's not just money, and a finance capable of thinking in years, not just in interest rates, because time isn't just what we spend or save, but what shapes the quality of collective life. So, returning to the title of our article, in a country where people live longer and longer, the real challenge will no longer be deciding when to retire, but how long we'll stay there, and what balance between activity and freedom we'll achieve. And perhaps, in this new map of life, the balance between time and value will become the most authentic measure of a civilization capable of enduring.

© Riproduzione riservata