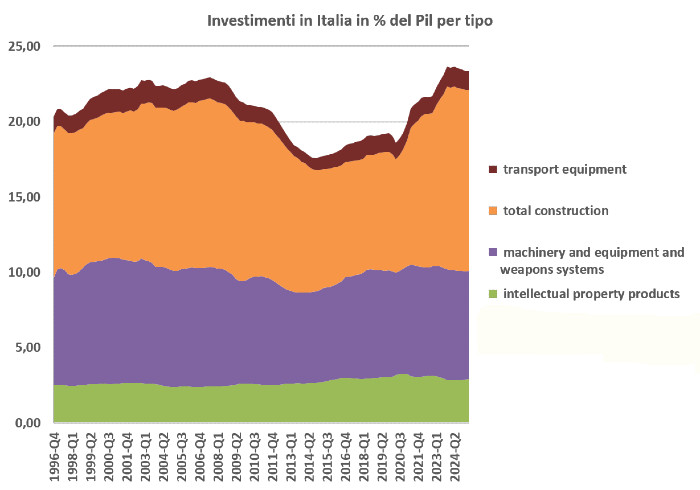

Italy stopped investing in its productive future long before the 2009 financial crisis exposed this fragility. ISTAT data show that total investment as a percentage of GDP will reach 22% in 2024, a seemingly respectable level compared to the low of 17% reached in 2013.

However, this recovery masks a profoundly unbalanced composition: almost all of the recent growth is attributable to construction, while investment in machinery, equipment, and intellectual property remains essentially stagnant relative to GDP.

The first graph clearly documents this phenomenon. The "total construction" component now represents approximately 10-11 percentage points of GDP, returning to pre-crisis levels after the collapse of the 2012-2019 period. By contrast, the "machinery, equipment, and weapons systems" component has hovered around 8-9 percentage points for thirty years, without any structural expansionary trend. The share of "intellectual property products" (including research and development and software) is even more modest, hovering between 2.5 and 3% of GDP. This pattern reveals an economy that has responded to recent fiscal stimuli, particularly the Superbonus and other construction incentives, by focusing resources on investments with low relative productivity and high levels of low-skilled labor intensity. Investments that drive technical progress, process innovation, and increased total factor productivity have, however, remained compressed, undermining the stated objectives of the Industry 4.0 plans and subsequent iterations of tax incentives for digitalization and automation.

The issue of investment financing is equally significant. Bank lending to businesses, historically the main source of external financing in Italy, has suffered a prolonged contraction since the sovereign debt crisis. According to Bank of Italy data, the stock of loans to non-financial businesses fell from approximately €900 billion in 2011 to approximately €700 billion in 2020, recovering only partially in subsequent years. The Italian stock market, measured by market capitalization relative to GDP, remains among the smallest in Europe, fluctuating around 30-35% of GDP compared to 100% in France or 60% in Germany, drastically limiting the possibilities for financing through the stock market.

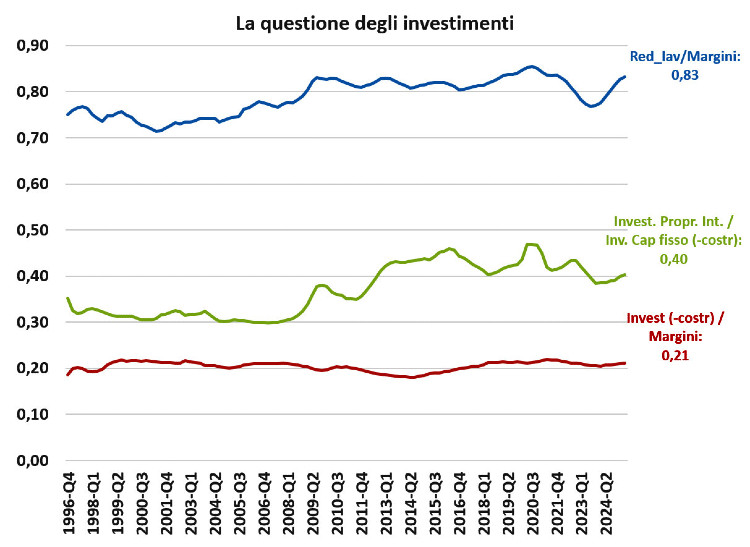

Regarding domestic financing, the second chart offers an illuminating analysis. The ratio of labor profitability to gross operating margins (Red_lav/Margini) remained stable between 0.72 and 0.85 over the period considered, settling at 0.83 in 2024. This stability indicates that the functional distribution of income between wages and profits has remained essentially constant, contrary to the narrative of excessive wage compression in favor of profits. The increase in wealth inequality, documented by the evolution of the Gini index of financial wealth, therefore arose primarily from the accumulation of rents rather than corporate profits: government bonds with guaranteed returns, stock price revaluations induced by ultra-expansionary monetary policies, and the appreciation of real estate assets. The most surprising finding emerges from the ratio of investments net of depreciation and gross operating margins (Investiments - costr/Margini), which remained stable at around 0.20-0.21. This means that Italian companies have consistently allocated only one-fifth of their margins to net investments, while the remaining four-fifths have been absorbed by distributions to shareholders, repayment of past debt, or liquidity accumulation.This behavior signals a revealed preference for asset preservation rather than production expansion.

Particularly worrying is the trend in investments in intellectual property. The ratio of intangible investments to investments in machinery (Invest. Propr. Int. / Inv. Cap fisso - costr) rose from approximately 0.30 in the second half of the 1990s to 0.40 in the period 2012-2020, before stabilizing without further progress. In absolute terms, for every 100 euros invested in machinery, Italian companies now invest 40 euros in research, development, and software, compared to 60-80 euros in more advanced economies. Furthermore, this intangible component had shown sustained growth until 2016, only to lose momentum just when industrial policies claimed to encourage it.

The macroeconomic implications of this productive underinvestment are evident in the growth performance of Italian GDP. Between 2000 and 2024, Italy's real GDP grew by approximately 7% overall, compared to 35% in Germany, 40% in France, and 50% in Spain. Total factor productivity, which measures the efficiency with which capital and labor are combined, remained essentially stagnant or even slightly declining according to OECD estimates. Without adequate accumulation of technology-intensive physical capital and sufficient investment in intangible assets, the Italian economy was unable to benefit from the efficiency gains associated with the digital revolution and automation.

Tax incentive policies for investment, from the Industry 4.0 plan launched in 2016 to subsequent implementations, have not produced the desired additivity. Tax credits for investments in new capital goods, although they have reached considerable size (over €10 billion annually in the 2020-2022 period), appear to have replaced rather than complemented investments that companies would have made anyway. The lack of growth in the share of productive investment in GDP, despite these massive incentives, suggests that constraints on financing and investment are deeper and more structural than supply-side policies assumed.

The situation is different for construction incentives, which have indeed generated additional investment, as demonstrated by the jump in construction from 2020 to 2023. The 110% Superbonus, in particular, has generated cumulative spending estimated at over €120 billion, with a direct and visible impact on the construction component of total investment. However, these investments have different economic characteristics: shorter duration, limited technological content, and a smaller impact on the economy's aggregate productivity. Energy retrofitting of buildings produces environmental benefits and improved living comfort, but does not increase the economy's productive capacity to the same extent as an investment in a new automated plant or an advanced information system. The financial structure of Italian firms helps explain this reluctance to invest in productive capital. The debt-to-GDP ratio of Italian non-financial corporations, although declining since its peaks in 2012-2013, remains high by historical standards. The prevalence of small and medium-sized enterprises, often family-run, is accompanied by a greater aversion to financial risk and a preference for self-financing over debt or equity markets. This institutional configuration, which in the past had guaranteed flexibility and resilience, has become an obstacle to growth and capital accumulation in technology-intensive sectors that require significant investment and a long time horizon.

International comparisons confirm Italy's unique characteristics. According to Eurostat data, the share of gross fixed investment in GDP in the European Union stands at 22-23%, similar to the Italian figure, but with a radically different composition. In Germany, the share of investment in machinery and equipment exceeds 7% of GDP, while that in intellectual property approaches 4%. In France, intangible investment represents over 4.5% of GDP. These countries have maintained or increased their productive investment intensity even during the crisis, while Italy has experienced a progressive, creeping deindustrialization masked by the nominal stability of the investment-to-GDP ratio, thanks to the contribution of the construction sector.

Future prospects will depend on the Italian economic system's ability to reverse this structural trend. The National Recovery and Resilience Plan allocates significant resources for the digital and ecological transition, with particular attention to investments in research, development, and innovation. However, the effectiveness of these interventions will depend on the ability to overcome the constraints that limited the impact of previous policies: fragmentation of the productive fabric, insufficient integration between public research and businesses, rigidity of the labor market for advanced technical skills, and an undersized capital market.

The lesson emerging from the data is clear: sustained economic growth requires capital accumulation oriented toward high-productivity components, particularly advanced machinery and intangible assets. Construction investments can provide a cyclical boost to aggregate demand and employment, but they do not lead to a permanent increase in the economic system's productive capacity and productivity. Italy has favored the first strategy, paying the price of structurally inferior growth compared to its European partners. Reversing this trend requires

It requires not only better-targeted tax incentives for scarce capital, but also measures to reduce competing rents from the most useful investments, a more fluid financial system that is less stingy with investments, and corporate-sized enterprises capable of tackling complex tasks, as well as improvements in ultra-protective corporate governance and the quality of human capital. Without these structural changes, which together would constitute a true industrial policy platform, the productivity and income gap compared to the most dynamic economies is destined not to narrow and, perhaps, to widen further.

Bibliography and sources

ISTAT, Conti economici nazionali, serie storica investimenti fissi lordi per tipo di bene, 1995-2024.

ISTAT, Conti economici nazionali, serie storica margini operativi lordi e redditi da lavoro dipendente, 1995-2024.

Banca d'Italia, "Relazione Annuale", vari anni, dati su prestiti bancari alle imprese non finanziarie.

Eurostat, National Accounts Database, Gross Fixed Capital Formation by asset type, 2000-2024.

OECD, Productivity Statistics, Total Factor Productivity growth rates, 1995-2023.

Ministero delle Imprese e del Made in Italy, "Rapporto annuale piano Industria 4.0", edizioni 2017-2023, dati su crediti d'imposta per investimenti.

Agenzia delle Entrate, "Superbonus 110%: dati e statistiche", rapporti periodici 2021-2024.

© Riproduzione riservata