Having exhausted the demographic boost from the baby boom and achieved the living standards of mass consumer societies by the late 1990s, Italy's economy has suffered a dramatic loss of GDP momentum, driven by weakness in the very factor that should power mature economies: labor productivity.

According to the 2025 Annual Productivity Report from Italy's Consiglio Nazionale dell'Economia e del Lavoro (CNEL), labor productivity crawled ahead at just 0.2% annually from 1995-2024—a dismal performance compared to the EU27's 1.2%, Germany's 1.0%, and France's 0.8%. The stagnation has only deepened in recent years, with productivity actually contracting 0.1% annually from 2019-2024, while growth has been propped up almost entirely by throwing more workers at the problem (+1.2% annual labor input expansion). This quantity-over-quality approach to growth signals Italy's fundamental failure to transition to the productivity-driven model that separates thriving advanced economies from also-rans.

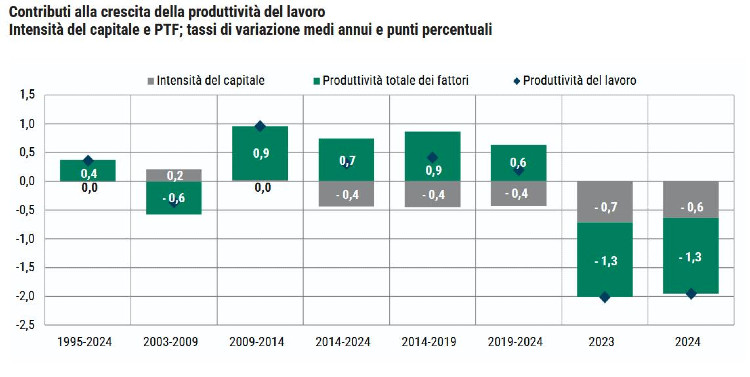

The productivity decomposition analysis reveals three critical interconnected factors.

First, capital intensity provided no significant boost to labor productivity growth over the long term, contributing zero from 1995-2024. ICT capital contributed only +0.1 percentage points, non-ICT physical capital had a negative impact (-0.1 p.p.), and intangible capital contributed nothing. In 2023-2024, both contributions—total factor productivity and capital per hour worked—turned negative (-0.7 p.p. and -0.6 p.p. in 2024), causing a 2.0% drop in labor productivity—a cold shower on an already weak Italian economy.

Second, Italy shows significant lag in intangible investments. An analysis of productivity impact by capital type reveals that only ICT capital has a positive contribution, though modest (+0.1% in 1995-2024), while non-ICT physical capital has negative impact (-0.1%) and non-ICT intangible capital is zero. This highlights serious delays in accumulating and efficiently using intangible capital—software, R&D, organization. Italy is the only major European country where, in the decade 2014-2023, tangible investments exceeded intangible ones, reversing the general trend of advanced economies. The share of intangible investments in GDP remained nearly stagnant between 1995 and 2023, rising from 7% to 8.4%, while in France it climbed from 11% to 16%. The growth sources analysis confirms that intangible capital's contribution to productivity remained chronically low and stable (from +0.23 in the pre-crisis period to +0.26 in 2014-2019), against the vertical collapse of tangible capital's contribution (from +0.71 to +0.02). Total factor productivity, after being negative in the pre-crisis period (-0.56), remained stagnant (+0.04) in the 2014-2019 recovery phase. After the pandemic crisis, Italy shows the opposite dynamic compared to other European countries: tangible investments overtook innovative capital accumulation, highlighting difficulty keeping pace with the innovation frontier.

Third, policies have boosted demand in low-productivity sectors. But the sectoral composition of economic growth obscures structural problems. Employment grew 63% in low-productivity sectors like construction, healthcare, social assistance, and restaurants, while remaining stagnant in high-productivity sectors. In the South, these sectors absorbed over 70% of new employment. Productivity per hour worked fell 0.9% in 2024 against a 1.6% increase in employment.

The dimensional structure of companies amplifies these imbalances. 94.7% of companies have fewer than 10 employees and over half of workers are employed in companies with fewer than 20 employees. Micro-enterprises contribute 41% to total employment versus the European average of 27%, but only 22.4% of turnover. Productivity differentials between large and small companies are marked: in manufacturing, large companies are over 70% more productive than medium ones, in ICT services the gap exceeds 80%.

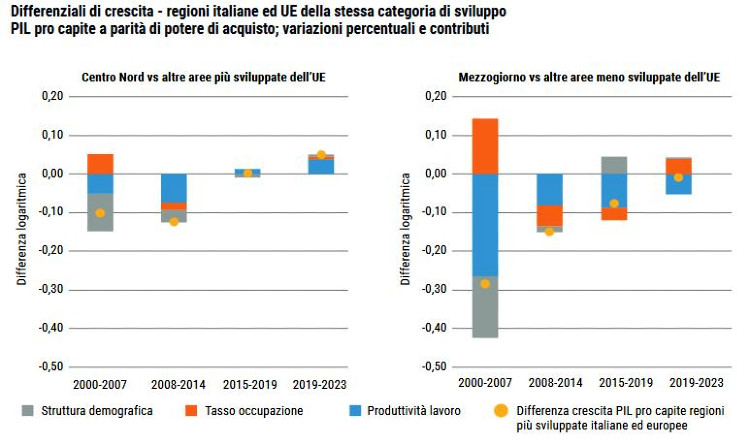

Territorial gaps represent another structural brake. The South recorded almost zero per capita GDP growth (+0.02% annually) in 2000-2023, against +0.2% in the Northwest. In per capita GDP decomposition, labor productivity provided negative contribution in 2000-2007 in the South, while supporting growth in other macro-areas. Southern regions show lower incidence of employment in high-tech sectors and knowledge-intensive services.

The analysis of productivity determinants shows how deep the problem roots run. Starting with skills: only 16% of workers have high ICT skills versus 30% in Germany and France, and only 15% of graduates are in STEM disciplines versus a European average of 26%. Only 38% of companies use ERP or Cloud solutions, twenty points below the European average, and 32% of companies made no digital investments in 2021-2024.

Then there's the size issue: micro-enterprises invest less in physical capital, innovation and technology, participate little in global value chains, and adopt less efficient management practices. Thus, only 17% of manufacturing companies export, and about half of exported value comes from 1% of exporters. Companies conducting innovative activity are 57% of the total, but only 23.7% invest in research and development.

The effect of labor reallocation between companies of different sizes contributed positively to productivity growth in 2014-2019, but this process lost momentum after the pandemic. In the ICT sector there was a recovery in reallocation toward large companies, but the sector's limited weight reduced the overall effect.

International comparison shows how Italian regions, both developed and less developed, have lost ground compared to European counterparts, with systematically negative contribution of labor productivity to the growth differential. The North-South gap exceeds 20% even with equal sector and company size, reflecting deficiencies in human capital, infrastructure, and institutional quality.

Recent dynamics confirm the persistence of structural problems. Between 2022 and 2024, labor productivity decreased 1.8% in 2023 and 1.4% in 2024, while hours worked increased 2.5% and 2.1% respectively. Growth was driven by the volume of labor employed rather than increased efficiency, with a development model that favors quantity over quality of the productive factor.

The effervescent dynamics of products made in Italy involved relatively few companies, which led the relative growth of exports in volume and unit values until 2019, spreading a perception of well-being that obscured the weak link of the Italian economy as a whole. The convergence of neo-protectionism and wars, with reduced security and increased costs and uncertainty in transportation times, has reduced the value of the foreign engine to which our economy was anchored for two decades. In the recent short term, the economy and general employment have benefited from the boost first from building bonuses then from the NRRP, as well as from international tourism growth, favored by mostly behavioral reasons (less attention to luxury goods and more attention to wellness consumption by global upper middle classes), but these elements not only haven't remedied structural problems, but are delaying awareness of the depth of certain structural gaps.

© Riproduzione riservata